Pakistani Terror Group Lashkar-e Tayyiba Extends Tentacles in United States

The recent confession

by David Headley, a Chicago Pakistani-American, that he scouted targets

for Lashkar-e Tayyiba's deadly attacks in Mumbai, India provides just

the latest evidence that the Pakistan-based terrorist group has expanded

into a worldwide threat -- and increasingly is recruiting U.S.

residents as participants in its murderous campaign.

The recent confession

by David Headley, a Chicago Pakistani-American, that he scouted targets

for Lashkar-e Tayyiba's deadly attacks in Mumbai, India provides just

the latest evidence that the Pakistan-based terrorist group has expanded

into a worldwide threat -- and increasingly is recruiting U.S.

residents as participants in its murderous campaign.While still described as a "farm team for al Qaida," the Pakistani group is rapidly honing its own credentials in the major leagues of Islamic terrorism.

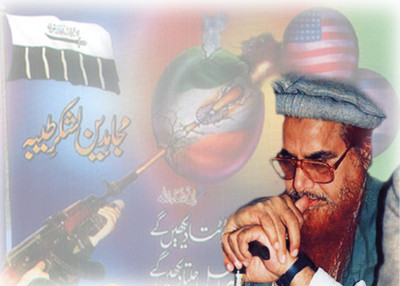

A new analysis of Lashkar's history prepared by the Investigative Project on Terrorism (IPT) documents the group's evolution since its 1989 founding as a proxy of the Pakistani government's conflict with India, providing recruits to push the Islamic insurgency in Indian Kashmir. Read the full report here.

Early on, it notes, Lashkar's focus was broadened to include a generalized campaign of terror against the West. By 2003, a founder of the group, Hafiz Saeed, urged his followers to "fight against the evil trio: America, Israel, and India." Broadening its base of operations, today the group has coordinated attacks on Western forces in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The report discusses increased cooperative efforts by Lashkar with al Qaida and other terrorist groups -- the Afghan Taliban, Tehrik-i-Taliban (the Pakistani Taliban), Harakat-ul-Jihadi-Islami and Jaish-e-Muhammad. Meanwhile, Pakistan has been slow to act against the group and its various fronts, with some government ministers offering unabashed praise.

Moreover, the IPT analysis details the shift to expanded recruitment in the West. Among those who passed through Lashkar training camps it cites an Australian-born al Qaida operative named David Hicks, convicted "shoe bomber" Richard Reid, and Dhiren Barot, who planned a failed gas-cylinder bombing in London.

The report focuses most closely on four recent successful efforts to shut down homegrown U.S. jihadists like Headley -- terrorists who journeyed overseas to Lashkar training camps, and participated in operations starting with those of the so-called "Virginia Paintball Jihad Network" and culminating in the 2008 attacks on train stations, hotels, restaurants and other public sites in Mumbai that killed 166 people, including six Americans.

The "Paintball" case that began a decade ago still ranks as the largest known American-based terror cell connected to Lashkar. By the end of the Justice Department's investigation, more than a dozen conspirators had been implicated. All but two of them were found guilty on charges related to their support for and participation in a Lashkar plot to carry out attacks against U.S. troops in Afghanistan, and sentenced to lengthy prison terms.

The entire conspiracy was initiated in 2000 when one of its members, Randall Todd Royer, travelled to Pakistan to attend a Lashkar terrorist training camp. He and his fellow jihadists earned the "paintball" soubriquet when they decided, soon after his return from Lahore, to use that game as a way of preparing for jihad.

The "games" were initially played at public courses, but eventually were moved to private farmland in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, to avoid suspicion.

Within weeks after al Qaida's 9-11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon the following year, other members of the group followed Royer's path to Pakistani camps, where they advanced from their paintball pursuits to training in using such weapons as AK-47 rifles, machine guns, anti-aircraft guns and rocket-propelled grenades.

The 2004 indictment of one of the group's ringleaders, Ali Al-Timimi, indicates that he spurred on his colleagues with assurances that they would die as martyrs if they were killed fighting Americans in Afghanistan. He recommended Lashkar as the group with which to affiliate, the records show, because "its belief system was good and it focused on combat."

Sentencing Al-Timimi to life in prison the following year, Judge Leonie Brinkema stressed the threat posed by Lashkar and its U.S.-based recruits. "I don't think that any well-read person can doubt the truth that terrorist camps are an essential part of the new terrorism that is perpetrated in the world today…People of good will need to do whatever they can to stop that," she declared.

In 2005, agents of the FBI Terrorism Task Force uncovered evidence that another group of American homegrown would-be jihadists had sought out Lashkar for training in terrorism. Working largely through a confidential informant, the Bureau developed information that led to the indictment and conviction of four conspirators on charges of providing material support to Lashkar and related terrorism offenses. They received prison sentences ranging from 13 to just under 30 years.

Yet a third plot involving domestic terrorists setting up a Lashkar training connection in the post-9-11 period was discovered, this one based in northwestern Georgia.

Investigation of this case uncovered a new wrinkle that demonstrated the global reach terrorist groups have attained in the age of the Internet. Those involved, it was discovered, had used Internet messaging to develop relationships and maintain contact with each other and with likeminded supporters of violent jihad in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Pakistan, Bosnia and elsewhere.

Thus, according to federal prosecutors, they discussed with Canadian counterparts plans to carry out attacks in the two countries and abroad, identifying "strategic locations in the United States that were suitable for terrorist attack, including military bases and oil storage facilities and refineries."

They discussed specific plans to attack the Dobbins Air Reserve Base in Marietta, Georgia, the 2006 criminal indictment charged, and later travelled to the Washington, D.C. area to scout possible targets. There they took video recordings of symbolic and infrastructure targets including the U.S. Capitol, the headquarters of the World Bank, the Masonic Temple in Alexandria, Virginia, and fuel storage tanks near a major highway in Northern Virginia. The videos were sent via an encrypted e-mail to an al Qaida operative in Britain.

Convicted in 2009 of conspiring to provide material support to Lashkar, the two Georgia men were sentenced to, respectively, 13 and 17 years in prison.

Disturbing tales of nascent terrorism, one and all. But they pale in outright viciousness -- and effectiveness --when compared with the case involving Chicagoan David Headley.

Headley was far from a novice terrorist in late 2006 when, records show, he began his specific task of scouting targets for Lashkar's planned attacks on a range of targets in Mumbai, India.

Born in 1960 in Washington, D.C., the son of a Pakistani father and an American mother, Headley had become sufficiently radicalized by early 2002 that he made repeated trips to Lashkar sites in Pakistan to receive paramilitary training.

To create a cover for his upcoming trips to India, he changed his last name, Gilani, to his mother's more American-sounding maiden name, Headley, and he arranged with co-conspirator Ahawwur Hussain Rana, a Pakistani-Canadian, to pass himself off as an employee of Rana's company, First World Immigration, to justify his numerous trips.

Even as his Mumbai assignment was gathering steam, Headley had been deeply involved in planning an attack against Jyllands-Posten, the Danish newspaper that had alienated many Muslims by publishing what were deemed offensive cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad.

That plot was largely deferred as he took on his Lashkar assignment, taking multiple trips to India during which he took video footage of such sites as the Taj Mahal and Oberoi hotels, the Leopold Café, the Nariman House and the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus train station.

In preparation for an attack by sea, he followed Lashkar's instructions to take more videos on an April 2008 series of boat trips in and around the Mumbai harbor; he then returned to Pakistan to offer his recommendations for potential landing sites.

Headley's efforts came to fruition on November 26, 2008, when 10 attackers trained by Lashkar carried out multiple assaults over a two-day period. Using guns, grenades and improvised explosive devices, they terrorized Mumbai, gunning down more than 160 innocent civilians at a train station, hospital, two five-star hotels, a Jewish center and a restaurant frequented by Westerners.

By the start of 2009, Headley was once again fully focused on the projected attack on Jyllands-Posten -- by then referred to as The Mickey Mouse Project, or MMP, -- in coded communications with Rana and others. But Lashkar withdrew from the plan due to an international crackdown in the wake of the Mumbai attacks.

Headley was arrested at Chicago's O'Hare International Airport on October 3, 2009 before the Mickey Mouse Project could be carried out, and Rana was arrested two weeks later.

Commenting on the arrests, David Kris, assistant attorney general for national security, called the case "a reminder that the threat posed by international terrorist organizations is global in nature and requires constant vigilance at home and abroad."

On March 18, 2010, Headley pled guilty to providing material support to Lashkar and a variety of other terrorism-related offenses. He has cooperated with the government in return for a commitment by the U.S. Attorney's office that it will not seek the death penalty. His sentencing has been deferred pending completion of his cooperation agreement.

Meanwhile, the Justice Department reported that he had been made available for extensive questioning by Indian investigators, who interviewed him over a seven-day period starting June 3, 2010.

Rana, who has pled guilty, remains in federal custody while awaiting trial.

And what can be done to curb the growing reach and increasing clout of Lashkar and similar Pakistan-based groups in the international terrorist firmament evidenced in all of these cases?

A comment by Bruce Riedel, a counterterrorism expert at the Brookings Institution in Washington, in an article published in the May 6, 2010 issue of TIME magazine puts the situation in sharp focus. The Administration's best approach, Riedel said, is to launch a "global takedown" of Pakistani jihad cells outside Pakistan, especially in Britain, the U.S. and the Middle East.

"These external bases are the most threatening to us, much more than their operations in Pakistan," he warned.

To read the full IPT report on Lashkar-e Tayyiba, click here.

Global Lessons from the Mumbai Terror Attacks

One

year after terrorists struck at the heart of India's financial hub,

Mumbai is still reeling from the shock of the attacks that left 183

people dead, including nine terrorists, and hundreds more injured. At

nightfall on November 26, armed terrorists came ashore in Mumbai, having

left the Pakistani port city of Karachi by boat. They attacked several

high profile targets throughout the city, including two luxury hotels –

the Taj Mahal Palace and the Oberoi-Trident – along with the main

railway terminal, a Jewish cultural center, a café frequented by

westerners, a movie theater and two hospitals.

One

year after terrorists struck at the heart of India's financial hub,

Mumbai is still reeling from the shock of the attacks that left 183

people dead, including nine terrorists, and hundreds more injured. At

nightfall on November 26, armed terrorists came ashore in Mumbai, having

left the Pakistani port city of Karachi by boat. They attacked several

high profile targets throughout the city, including two luxury hotels –

the Taj Mahal Palace and the Oberoi-Trident – along with the main

railway terminal, a Jewish cultural center, a café frequented by

westerners, a movie theater and two hospitals.Six Americans were among the 26 foreigners reported killed.

This was not a first for the city of Mumbai. In March 1993, several car bombs were set off at important landmarks across the city, including the stock exchange, killing around 250 people. In July 2006, another series of blasts ripped through Mumbai's commuter train network killing more than 200 people.

However, even having "been here before," the attacks that transpired on November 26th were not just more of the same; the 2008 attacks featured stark differences from the past and mark an important step in the evolution of urban terrorism in India. Terrorists for the first time employed frontal assault techniques and sophisticated technology, including global positioning system handsets, satellite phones, and Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) phone service to stay in touch with their handlers in Pakistan. Those handlers – watching events in real time on television – orchestrated the attacks from several thousand miles away. Before November 26th, terrorists used bombs triggered by timers to wage jihad on Indian cities, with the notable exception of an attack by five armed men on the Indian Parliament in December 2001.

"The Mumbai attacks last November were unprecedented in terms of scale and intensity," Brahma Chellaney, a top strategic expert at a leading think tank in New Delhi, said in an interview with the Investigative Project on Terrorism. "The terrorists were careful to choose those [targets] that would create rage across India." They "took on the rich and the wealthy in India by targeting those two luxury hotels, and by taking on a Jewish center in Mumbai, they took on some foreigners who were present in that Jewish Center in addition to those who were present in the two hotels."

"Even a year later now on the anniversary of the Mumbai attacks, India hasn't recovered from those attacks," Chellaney added.

Transnational Islamic terror comes of age

The Mumbai terror attacks mark the coming of age of global Islamic jihad. Reports linking the Mumbai attacks to arrests of terror suspects in Chicago and Italy, and evidence that a large part of the planning for the attacks took place in the U.S. and Pakistan, underscore the international nature of the attacks. Two Chicago men – a Canadian and an American citizen both born in Pakistan - for example, are being investigated by the FBI for their possible involvement in the Mumbai attacks. David Coleman Headley and Tahawwur Rana were arrested earlier this month on federal charges for their alleged roles in foreign terror plots that focused on high profile targets in India and Denmark. The FBI claims it has evidence the two men have links to Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), the Pakistani terror group believed to be behind the Mumbai attacks.

New Delhi has presented evidence to Pakistan that the attackers were trained in and came from Pakistan. Indian government sources have further confirmed that the National Investigative Agency (NIA) has found the Chicago suspects made calls to the same numbers as the LeT handlers in Pakistan who were in touch with the terrorists during the attacks. It has been disclosed that Headley visited India several times in the past three years and stayed at the Taj and Trident – the two hotels attacked on 11/26 – besides meeting with prominent Bollywood stars. Headley reportedly used his contacts with Bollywood stars as a cover for his reconnaissance missions and visited each of the targeted sites, including the Jewish Center, the main railway terminal, and the Leopold Café. Headley and Rana have further been reported to have strong ties to Pakistan, including close links with a former military officer in Pakistan. FBI affidavits also allege that Headley traveled to Pakistan to attend a terrorist training camp and meet with LeT leaders.

Trial of LeT suspects in Pakistan caught up in red tape

A Pakistani anti-terrorism court indicted seven suspects this week, including Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) operations chief Zakiur Rehman Lakhvi, for alleged involvement in the attacks but the trial has been caught up in red tape and confusion. Earlier this month, India handed Pakistan a seventh dossier of evidence on the Mumbai attacks that included depositions of a Mumbai judge before whom the lone surviving gunman in the attacks, Mohammad Ajmal Kasab, had confessed to being trained in Lashkar camps and claimed LeT operatives, including suspected mastermind Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi, plotted the attacks. The dossier included testimonies of FBI officers who confirmed that cell phones recovered from the terror sites were used by terrorists to communicate with their handlers in Pakistan at the time of the attacks.

The FBI had helped India decode conversations recorded between the attackers and their handlers in Pakistan during the attacks.

New Delhi has called on Islamabad to take action against Jamaat-ud-Dawah (JuD) leader Hafiz Saeed, founder of LeT, and another alleged mastermind of the attacks. Saeed remains free, however, and recently was reported to be preaching radical sermons at the Jamia al-Qadsia mosque in Lahore. Indian calls to Pakistan to act against the perpetrators of 11/26, including Hafiz Saeed, have been backed by the U.S. Ambassador in New Delhi, Timothy Roemer, who also called LeT a "global threat."

Indian calls for extradition of the terror suspects have been rejected by Pakistan.

The Pakistani intelligence service – a state within a state?

Analysts claim that Pakistan is not likely to dismantle terrorist infrastructure on its soil or to take action against the November 26th attackers. Pakistan's military establishment, including its Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency, has been accused of backing terrorist groups in Kashmir over the past two decades in a bid to wage a low-intensity proxy war against India.

"What India faces is state sponsored acts of terror by non-state actors from Pakistan, and behind this state sponsorship is one institution, the Pakistani intelligence called ISI. It is a state within a state. It is not answerable to anybody," Chellaney told the IPT.

Saeed, in fact, had the blessings of the ISI when he founded Lashkar-e-Taiba in 1990 to fight Indians in Kashmir. The group was banned by the Pakistani government in 2002 under U.S. pressure but continued to operate under the banner of Jamaat-ud-Dawah, an Islamic charity also founded by Saeed and accused of being a front for Lashkar-e-Taiba.

Chellaney highlights the current dilemma the civilian government in Islamabad faces to bring the perpetrators of the Mumbai attacks to justice:

"I don't think the Indians can have much hope that the Pakistanis will actually go after the key guys because in Pakistan we have a split authority, the government in power is run by civilians who're not involved in such acts of terror and they are by and large sincere in what they say. The problem in Pakistan is that the real institution, the one that is most powerful, and the one that is linked up with terrorists is the military establishment and that includes the intelligence organization called the ISI and these guys are not under civilian oversight."Lessons from Mumbai:

The Mumbai attacks can be instructive for the U.S. and other Western democracies, Chellaney said. "What happened in Mumbai in 2008 is a novel method that is likely to be replicated in the West before long."

India, he said, has "been used as a lab to try out new techniques of terror. And once those techniques of terror have been perfected in India, they have been replicated elsewhere."

For example, the 1988 Pan Am 103 bombing was not unique. In fact, "it was a copy of the similar bombing of the Air India Kanishka jetliner [in 1985], which also was bombed over the mid-Atlantic," Chellaney said. "Similarly, the attacks on city transportation systems, subways for example, on buses, trains, etc. were first tried out in Mumbai in the early 1990s and subsequently they were tried out in Europe and elsewhere."

Jihadists, Chellaney concluded, feel that "if they can shake the world's largest democracy, they believe they can shake any Western democracy."

India's trial of Mohammad Kasab, the sole surviving gunman in the Mumbai terror attacks, has relevance for the U.S. as it prepares to move 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed from a military detention in Guantanamo Bay to a federal trial in New York.

According to international security expert Chellaney:

"In India, every terrorist goes through a civilian court and therefore for an Indian it's a bit of a surprise that there's a lot of controversy in the U.S. about trying Khalid Sheikh Mohammed in a New York civilian court because that's a normal process in India… [The debate however] does open a question as to whether terrorists who are actually waging war against a country are entitled to the same rights that a citizen of a country has…. For example those who came to attack the United States at 9/11 were seeking to destroy the United States of America. They were seeking to undermine what it stood for, and therefore to grant them the same civil liberties that ordinary American citizens have does raise an interesting question and I think that we need to debate that question fully. But we need to have a more international standard on this because I don't think it really helps to have one standard in the U.S., another standard in Britain, a third standard in India."Asked about the lessons India learned from the attacks and the subsequent investigations, Chellaney honed in on the live, unfettered media coverage that was present as the massacre ensued:

"We should not black out coverage, but we should do it in a way that the media is not helping the terrorists because the terrorists in Mumbai were in link by telephone with their handlers in Pakistan who were watching live television and could actually warn these attackers in Mumbai of what was coming."The initial response was "pretty amateurish," according to Chellaney. Indian police were ill trained to deal with the attacks and commandos had to be flown in from New Delhi, which took several hours. But he sees progress: "Investigations since those attacks have been more professional ... crisis management procedures are better now so if there were to be another attack, the Indians would be more prepared to respond in a more professional manner."

No comments:

Post a Comment