Document Friday: Why Kissinger Thought the CIA was Blackmailing Him

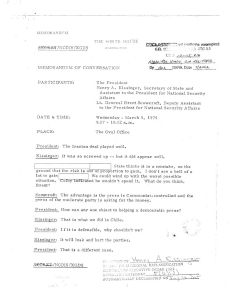

The CIA director was blackmailing the secretary of state; a nuclear deal with Iran was in the works; and the U.S. president wanted to pursue Middle East peace. President Gerald Ford and Henry Kissinger — then serving as both secretary of state and national security adviser — discussed all of this and more on the morning of March 5, 1975. Loyal assistant Lt. Gen. Brent Scowcroft took notes to provide this practically verbatim Secret memorandum of conversation, published here for the first time, which the National Security Archive obtained through a Mandatory Declassification Review request to the Gerald R. Ford Library.With this “memcon,” the reader can be a fly on the wall in the Oval Office, as Ford and Kissinger review issues that are familiar even now: from stalled Middle East peace negotiations to congressional investigations of the CIA, from oil prices and our leverage with the Saudis to covert operations involving assassinations.

Even the opening lines, about a “screwed up” Iranian deal, resonate today — the front page of that day’s New York Times heralded Iran’s commitment to spend $15 billion in the United States over the next five years, as announced by Kissinger and the Iranian finance minister, including “as many as eight large nuclear power plants in the next decade.” The Times story commented, “Iran has made a major policy decision to develop nuclear power, anticipating that her oil supply will decrease sharply in the next few decades. Iran has already agreed to buy two power plants from France and two from West Germany.”

The next section of the conversation refers to Portugal — although the country name has been redacted. It was no secret even in 1975 that the United States opposed communist participation in the Portuguese government and thought NATO was at risk from the Eurocommunism virus. Here, the debate was whether the CIA should covertly fund the non-communist press, just as the United States had in Chile. Kissinger was concerned that such aid would “leak and hurt the parties.”

The president, who later that day would meet with the leaders of the special Senate committee investigating CIA illegalities, asks whether he should warn committee chair Sen. Frank Church (D-ID) about leaks. At this point, Kissinger makes perhaps the most remarkable remark of the whole conversation: “[CIA director William] Colby is now blackmailing me on the assassination stories.” Kissinger goes on to explain: “Nixon and I asked [then CIA director Richard] Helms to look into possibilities of a coup in Chile in 1970 [against the newly-elected Marxist president Salvador Allende]. Helms said it wouldn’t work. Then later the people who it was discussed with tried to kidnap [army commander Gen. Rene] Schneider and killed him.”

Multiple investigations and reports — including an unsuccessful lawsuit by Schneider’s family — have tried to address this particular episode. The CIA’s own report to Congress, compelled by then Rep. Maurice Hinchey (D-NY) in 2000, acknowledged that the CIA and the U.S. government as a whole (meaning Kissinger and President Nixon as well) agreed with multiple potential coup plotters in Chile that Schneider’s devotion to the Chilean Constitution meant his “abduction… was an essential step in any coup plan.” CIA claimed, “We have found no information, however, that the coup plotters’ or CIA’s intention was that the general be killed in any abduction effort.” As Shakespeare wrote, methinks thou dost protest too much. After the fact, the CIA passed $35,000 to the murderers.

But here, Kissinger quickly changes the subject, to OPEC and its difficulties in allocating production cuts to keep the world price of oil high enough to meet each producing country’s income goals. He bemoans “this discrimination campaign of the Jews” for keeping the United States from getting a deal with the Saudis against cutting production (i.e., keeping oil prices lower).

Then they launch into the most extended part of the conversation, about the Middle East, the possibility of getting the parties to Geneva for negotiations, what Syrian dictator Assad would want, and how Israel’s recalcitrance was holding up progress. Kissinger says, “we just can’t go to Geneva as the lawyer for Israel.” Ford asks for “a good faith effort,” to which Kissinger responds, “A good faith effort is bound to fail…. Israel won’t even look at it.” Ford ups the ante: “A good faith effort to me is one where we put the screws on.”

This candid memcon testifies to the extraordinary historical value and contemporary relevance of the documentary record of Henry Kissinger’s years at the White House and the State Department, 1969 through 1976. The sheer volume of the Kissinger documentation qualifies for the Guinness Book — no top presidential adviser before or since has maintained such an extensive and practically verbatim record of his every conversation and meeting. Kissinger’s secretaries listened in on and memorialized in “telcons” more than 15,000 of his telephone calls from “dead key” lines, while his aides would stay up into the wee hours of the morning after talks with foreign leaders — or with the president himself — writing up from their own (and the interpreters’) notes the detailed memcons of the meetings, which number well into the thousands as well.

For 20 years after he left government, Kissinger succeeded in monopolizing access to these files, which he took with him in December 1976. He first sequestered these papers at the Rockefeller estate (in Pocantico Hills, New York) and only when reporters started asking questions and even filing Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuits, did he gift them as a closed collection to the Library of Congress — Congress having conveniently exempted itself from the FOIA. In the 1990s, when State Department historians began preparing the Foreign Relations of the United States documentary volumes on the Nixon years, they asked for access to the collection, which Kissinger granted (with significant restrictions — no photocopies, no note-taking), and in going through it, they found records that did not exist in the regular government files — even though Kissinger had claimed he only took copies when he left office.

There was a happy ending to this story, but not until my own organization, the National Security Archive, threatened to bring legal action against the State Department and the National Archives for abdicating their duty under the records laws, did the government finally ask Kissinger to return copies of the records, which he did in 2001. Securocrats are still declassifying some of the juiciest items, like this one.

No comments:

Post a Comment